Survey Says: Your Asset Manager’s Sell Discipline Stinks

The last time an asset manager told you about their buy/sell process, did the conversation sound a lot like what’s depicted in this pie chart?

It’s bewildering, considering building and maintaining an investment portfolio requires decisions about what to buy and sell. Yet, even elite institutional portfolio managers disproportionately focus on the first half of that equation.

It turns out that’s a quantifiably costly mistake.

A Dart-Throwing Monkey Can Sell Better Than Many Asset Managers

We’re able to better understand the scale of the problem thanks to a study released earlier in 2021, “Selling Fast and Buying Slow: Heuristics and Trading Performance of Institutional Investors.”

While there’s already extensive research about the impact of behavioral biases on individual investors, this study differs because it focuses on institutional portfolio managers. It sought to determine whether these top investors are also prone to non-rational decision making and, if so, the extent to which it affects portfolio performance.

The data showed that sophisticated market participants display skill in buying, but their selling decisions underperform – and substantially. The magnitude of the annualized outperformance of buys and underperformance of sales were statistically significant and economically meaningful. Whereas the average stock bought outperformed by 120 basis points over a one-year horizon, sold positions lagged by 80 basis points over the same timeframe.

Of course, to underperform, there needs to be a benchmark. In the study, the point of comparison was a random buy/sell strategy. That’s what makes the results so jarring. If an at-random decision-making model can perform better than elite portfolio managers, does that mean the proverbial dart-throwing monkey could sell assets just as well as someone with 20 years of experience managing institutional portfolios and an alphabet soup of financial designations? Yikes.

We imagine the eyes of our non-data-nerd readers may glaze over if we spend too much time illustrating the richness of the study’s data. But for our fellow data-dorks, be sure to check out our summary of how the authors tested whether biases cannibalize existing, still viable holdings.

Clients Invest Because of The Buy-Story & Rarely Ask About the Sell-Story

At face value, the fundamentals of buying and selling to optimize performance should be essentially the same. In practice, they are not.

Asset managers focus primarily on finding the next great idea to add to their portfolio. They’re incentivized to do so as well, since being able to present new investment ideas in a compelling narrative helps win and keep business. Selling, on the other hand, is largely viewed as a way to raise cash for purchases or cut losing positions.

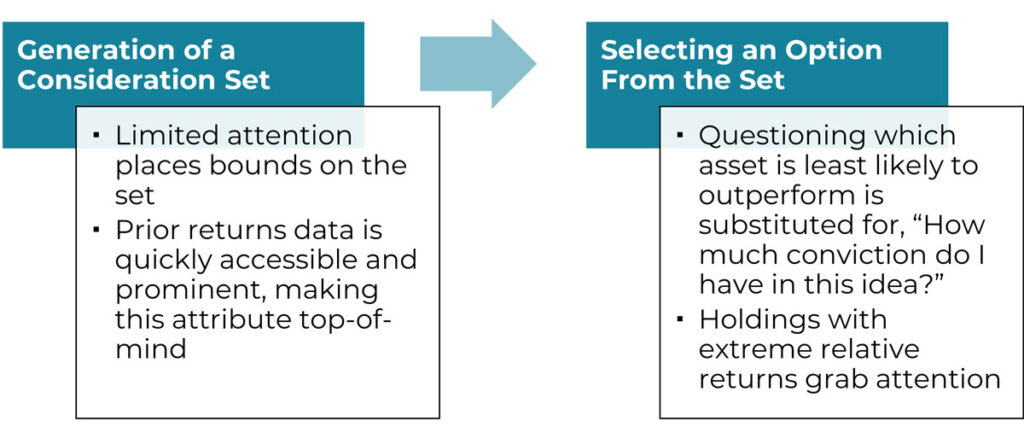

Even though the two decisions have similarities in terms of frequency, substance, and consequence for performance, the different psychological processes create fertile ground for non-rational decision making at each stage.

Stages of the Selling Decision-Making Process

The study demonstrates that positions with extreme returns are over-represented in consideration sets, and like retail investors, institutional portfolio managers ultimately are likely to sell them. Holdings in the top or bottom 5% based on prior returns are roughly 50% more likely to be sold relative to those that just over- or under-performed.

The same tendency did not show itself in the buy-side data.

It’s a little funny to me that we’re talking about an industry accustomed to slapping, “Past performance is no guarantee of future results,” disclaimers on anything that even kinda-sorta-maybe-might-almost reference any kind of investment result. And yet, portfolio managers rely on a stock’s near-term absolute performance data when making their own quick judgments about what to sell.

The ‘Simple’ Solution Might Run Against Human Nature

If lack of attention and over-reliance on performance data are culprits, then a simple solution to the selling problem would be to shore up these weaknesses, right?

Well, the study contains evidence that indicates it really could be that simple, particularly as it relates to increased attention. The findings suggest that when portfolio managers pay more attention to existing positions, such as on earnings announcement days, their consideration set is larger, the amount of information they consider is broader, and their selling performance improves substantially.

But there’s a bigger question the study doesn’t consider: Are human beings even capable of consistently combatting those two areas of weakness when it comes to selling?

We’re skeptical.

Pre-Determined Systems Won’t (Can’t!) Neglect Selling Discipline

At Blueprint Investment Partners, we think human biases are the biggest obstacle to successful investing, no matter where you fall on the continuum of retail investor to institutional PM. Our answer to the problem is to remove human behavior from the investing process wherever possible by pre-determining buying and selling decisions – and doing so long before a decision even needs to be made.

We accomplish this through a rules-based and repeatable systematic investing process that dictates which assets to buy and sell, when to enter and exit, and how much to transact.

This style of asset management was poorly represented in “Selling Fast and Buying Slow” simply because only 22 systematic, quantitative portfolios were available for the sample. Among the remaining 761 non-systematic portfolios, those least likely to apply quantitative data (i.e., fundamentals-oriented investment approaches) demonstrated the worst selling performance.

We think the explanation is simple: Humans can neglect selling discipline for all the reasons discussed in this blog, but processes cannot. A process doesn’t have competing demands on its time and attention. A process isn’t incentivized to emphasize the buy-story over the sell-story. A process doesn’t care if it’s earnings season. A process simply looks at the data (in our case, that data is price trends) and executes when, if, and how it’s supposed to.

Jon Robinson

Let's Talk

If you’d like to learn more about our systematic approach to asset management